Need Full Specifications?

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

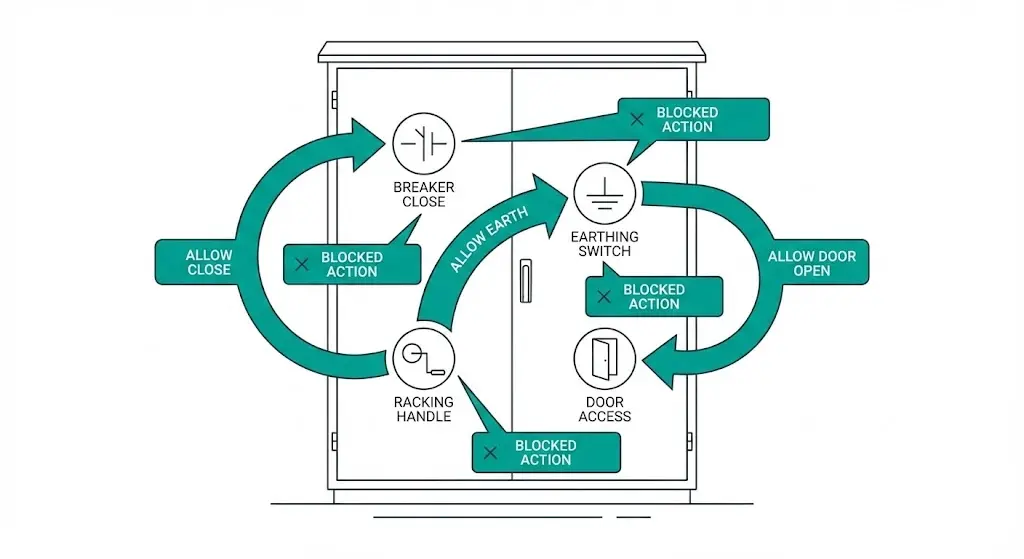

A safety interlock in medium-voltage (MV) switchgear is an engineered permission barrier: it prevents an unsafe operation sequence from being physically possible (mechanical interlock) or electrically permitted (control-circuit interlock). The goal is not convenience—it is to make dangerous sequences impossible, especially during outage work when people are under time pressure.

“Five-prevention” (5-prevention) is the practical framework used in many metal-enclosed lineups: it defines the specific misoperations that must be blocked, then ties each block to verifiable equipment states (breaker status, truck position, earthing status, door/access status).

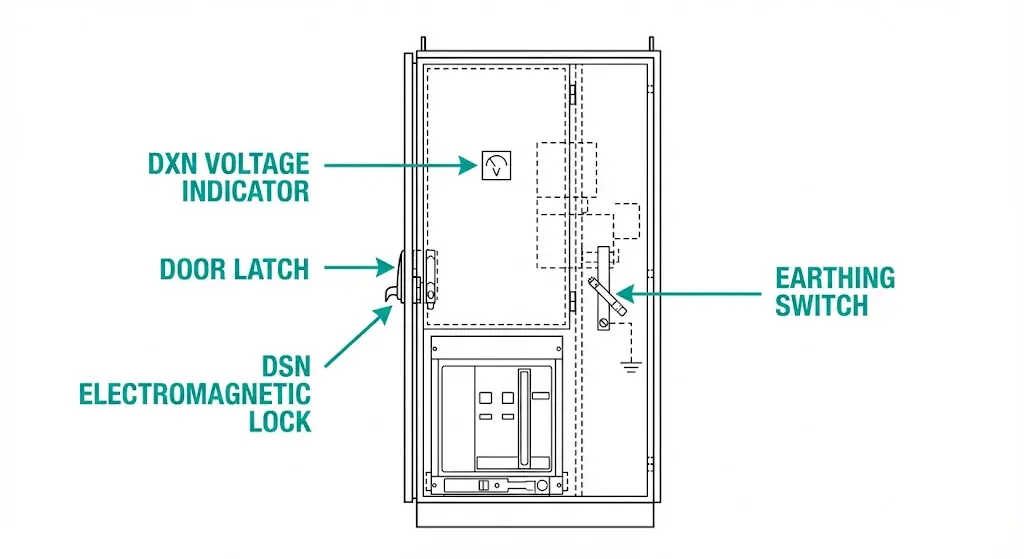

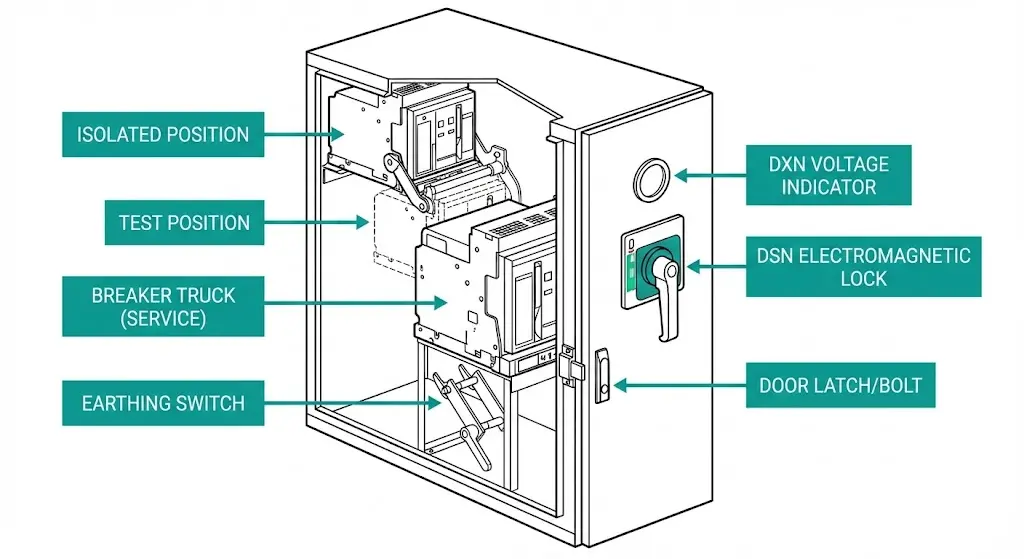

You will often see labels like DSN and DXN in drawings and site conventions. These names are not universal and should be read directly from the project schematics, but common usage is:

Most MV panels fall in typical voltage classes such as 12 kV up to 40.5 kV, while the interlock and indication circuits commonly run on 110 V DC or 220 V AC/DC control power (often 50/60 Hz for AC). Your interlock philosophy should be conservative: missing signals or conflicting feedback must default to NOT permitted for high-consequence actions (earthing, door access, racking, closing).

For standards context, the IEC 62271 family covers high-voltage switchgear and controlgear; IEC 62271-200 addresses AC metal-enclosed switchgear and controlgear. Authority reference: IEC 62271 series (IEC Webstore).Internal reference (non-competing context): Switchgear Component Manufacturer.

Five-prevention only works when it is written as “you cannot do X unless state Y is proven.” Below is a practical checklist that can be used as an operations/commissioning reference across different MV lineups.

[Expert Insight]

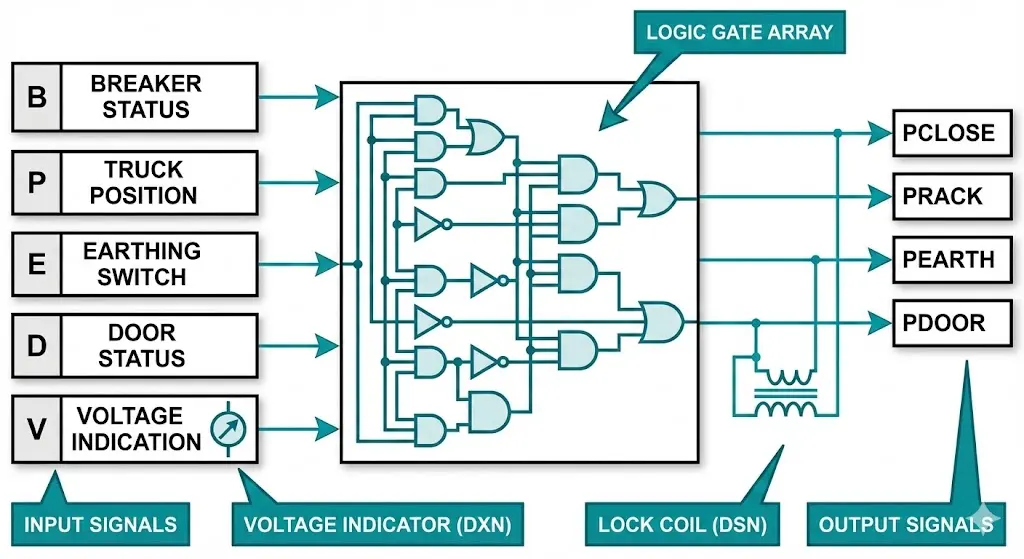

A robust interlock scheme is a state machine. DSN (lock coil) is typically an output device that physically prevents a handle/door/operation; DXN (voltage indication) is typically an input that informs whether “live” might still exist. Neither should be treated as a single point of truth.

Use a defined set of inputs (states) and outputs (permissives), and then validate them during commissioning with “wrong action” attempts. Typical inputs:

Typical outputs:

A readable matrix (example) shows how the panel should behave:

*Many lineups add extra requirements such as key release, shutter position, or latch engagement before PEARTH/PDOOR becomes YES.

The rule to protect people is consistent: for high-consequence operations, missing input = NOT permitted and disagreement = NOT permitted, even if that creates nuisance blocks that must be resolved by proper sensing and wiring discipline.

Five-prevention is enforced by hardware. A scheme is only as safe as its weakest enforcement point.

Mechanical key interlocks (trapped key / key exchange / linkage)

Best at creating a hard, power-independent barrier for access and earthing. They physically prevent motion of door bolts, earthing handles, or racking handles. Typical issues are wear and alignment: sticky cylinders, bent cams, door sag, or poor key control.

Electrical interlocks (aux contacts, position switches, relays, DSN-type locks)

Best at combining multiple states and supporting remote operation. They can also create evidence (alarms/logs). Typical issues are maintenance drift: miswired aux contacts, swapped NO/NC logic, stuck relays, or permissives that go true when a signal is missing.

Practical comparison (what engineers should care about):

[Expert Insight]

Operators follow sequences, so commissioning should verify that the lineup forces the safe sequence every time.

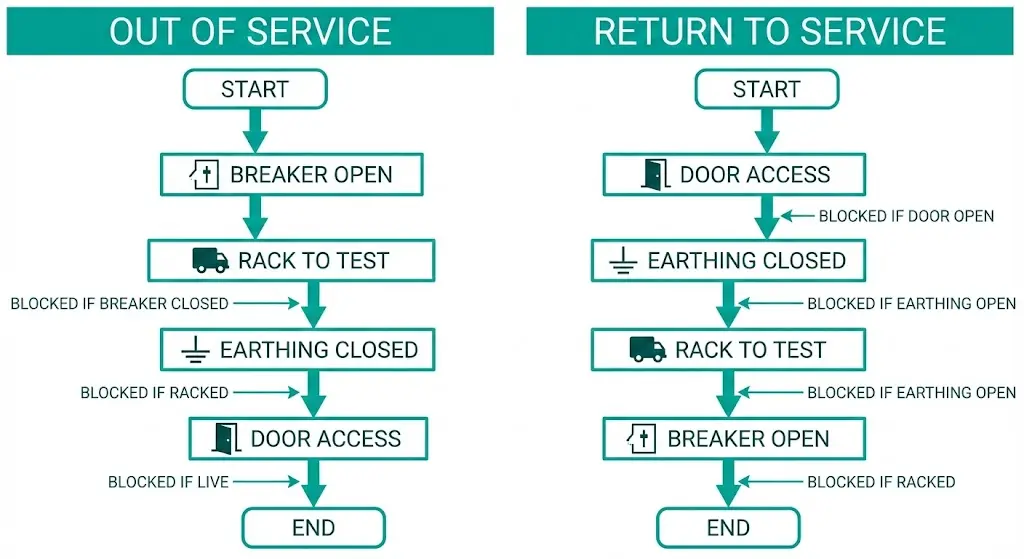

Sequence A — taking a feeder out of service (isolate + earth + access):

Sequence B — returning to service (close only when safe):

Common field failure points to actively look for:

Interlocks usually fail partially. Commissioning and periodic maintenance should treat five-prevention as a system with pass/fail outcomes.

Mechanical checks (control power OFF is fine):

Electrical checks (control power ON):

Misoperation simulation (the test that matters):

Try the forbidden actions—close with earthing CLOSED; earth with breaker CLOSED; rack with breaker CLOSED; open door in unsafe states. PASS only if the lineup blocks them reliably and repeatably.

Operational discipline completes the system: any temporary bypass should be logged, tagged, time-limited, and followed by a full interlock re-test after restoration.

Retrofits make sense when your lineup’s “allowed actions” no longer match how the site operates: repeated near-misses, frequent nuisance blocks that drive bypass behavior, mixed-vendor replacements that break the original permissive chain, or adding remote operation without upgrading access/earthing enforcement.

Procurement/spec items (write them so they can be tested):

Acceptance tests (witnessed and recorded):

Share your single-line diagram and the interlock drawings. XBRELE can convert the DSN/DXN scheme into a testable permissive matrix, identify bypass-prone points, and return a commissioning checklist your operators can execute with confidence.

1) Is “five-prevention” the same thing as a key interlock?

Not exactly; five-prevention is the safety logic target, while a key interlock is one hardware method used to enforce part of that logic.

2) Can voltage indication alone be used to permit earthing?

It may support decisions, but many schemes add position and breaker-status confirmations so one failed signal doesn’t create a false-safe condition.

3) Why do some lineups block operations even when the operator believes it’s safe?

Conservative logic will block when it cannot prove the required state; the fix is usually better state sensing, wiring discipline, or mechanical alignment—not removing the block.

4) What’s the quickest way to catch a dangerous interlock defect during commissioning?

Use a written permissive matrix and physically attempt the forbidden actions under controlled conditions.

5) Do remote-operated panels reduce the need for physical interlocks?

Remote operation reduces exposure, but access, earthing, and racking still need hard prevention against unsafe sequences.

6) What should a site do if an interlock must be bypassed temporarily?

Treat it as a controlled deviation: label it, record who applied it and why, set a removal time, and re-test the full interlock sequence after restoration.