Need Full Specifications?

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

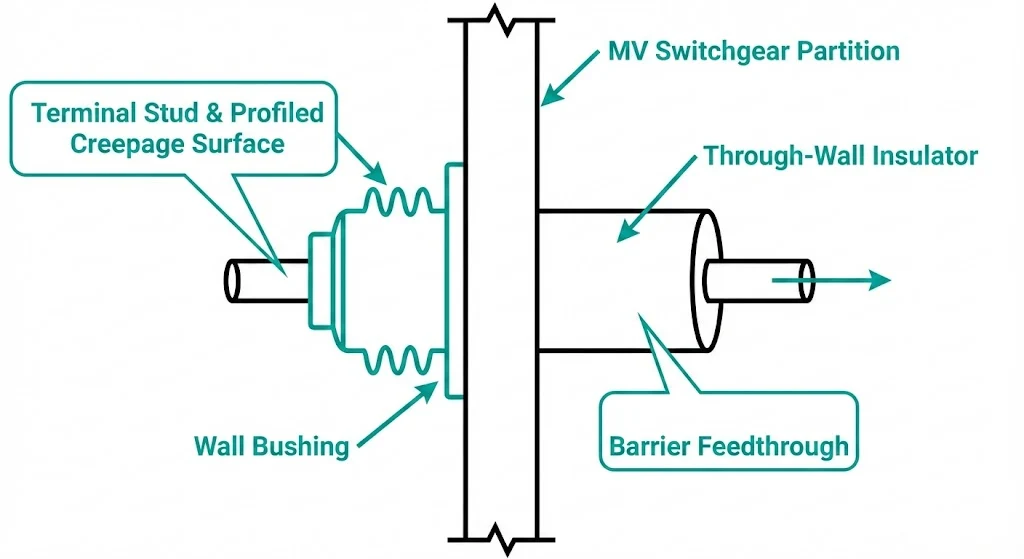

A wall bushing is an insulated primary-conductor feedthrough that carries a conductor through a grounded barrier (panel, partition, or tank wall) while controlling electric stress at the wall edge. It is typically a small system: conductor (rod/tube/stud), insulation body (epoxy/resin/ceramic/polymer), and a defined terminal interface (studs, pads, lugs, busbar faces). In MV switchgear you commonly see it applied around system classes such as 12 kV and 24 kV, where wall cutout geometry, creepage shaping, and terminal hardware edges can matter as much as bulk insulation thickness. For bushing products above 1 kV, IEC 60137 is commonly referenced for bushing ratings and test practices.

A through-wall insulator (through-partition insulator) is primarily an insulating barrier component that maintains dielectric separation across a wall. It can include a passage for a conductor or cable, but it does not automatically include a bushing-style terminal system or a current-rated interface; its design emphasis is insulation continuity and sealing at the penetration.

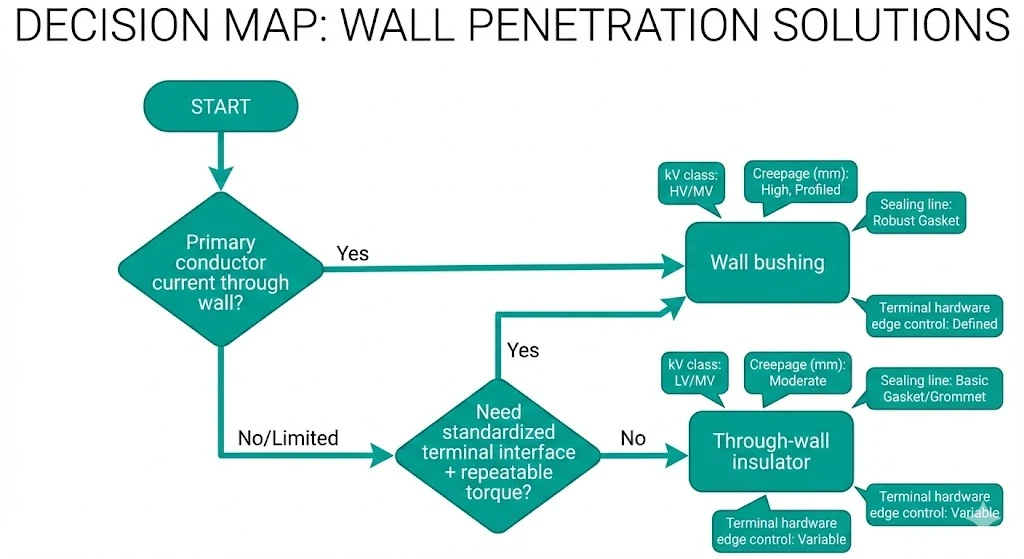

What a wall bushing is not: a generic grommet or sleeve. If there is no controlled terminal/electrode geometry and no attention to the grounded wall edge, it is not doing bushing work. What a through-wall insulator is not: a guaranteed drop-in substitute when you need repeatable torque joints and a defined current path.

Both parts can look like “an epoxy cylinder in a steel wall.” The difference is what the design controls versus what it leaves to assembly.

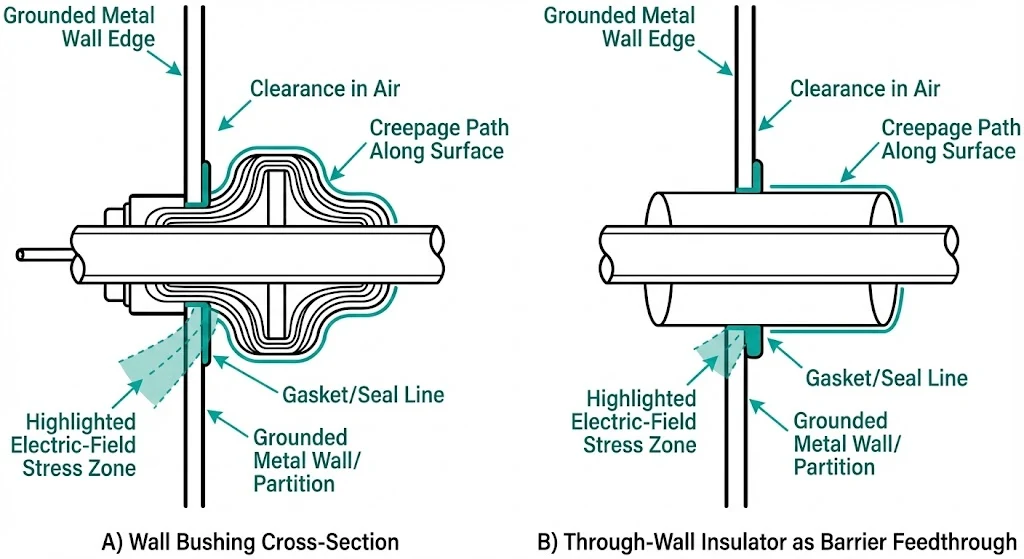

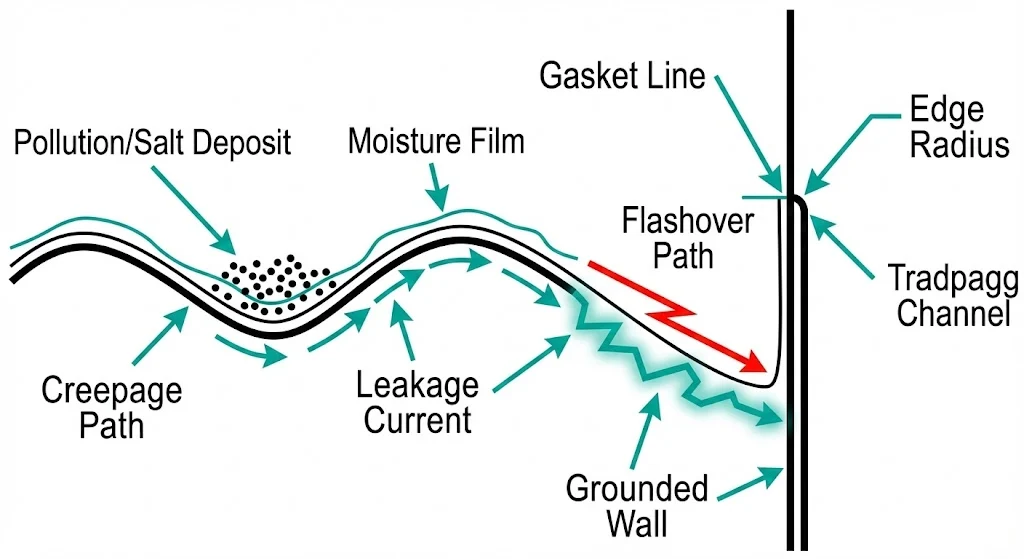

A wall bushing is built around a defined electrode system: the conductor and its terminal hardware set equipotential surfaces that shape the local field. The dielectric path is engineered through interfaces—metal → solid insulation → surface/air → grounded wall—so geometry decides where stress concentrates. As an illustrative example, a sharp burr with an effective radius near 0.5 mm can significantly intensify local stress compared with a more radiused edge around 3 mm, depending on spacing and hardware shape. This is why many bushing designs “spend” geometry budget near the wall transition.

A through-wall insulator behaves more like a barrier. It prioritizes insulation continuity through the wall and sealing integrity. If terminal electrodes are not controlled by the component, the stress picture can be dominated by “field hardware”: lug stack shape, washer selection, busbar pad edges, and how close metal sits to the grounded wall.

Service-relevant differences to look for on the drawing:

For PD measurement language, IEC 60270 is the commonly used reference for the measurement method (test circuit concepts and calibration).

Use this table to lock the decision to checkable parameters (drawing + datasheet), not naming.

| Decision parameter | Wall bushing (typical) | Through-wall insulator (typical) | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| System class | Explicit (e.g., 12 kV, 24 kV) | Explicit, sometimes barrier-focused | Aligns with insulation coordination |

| Impulse / BIL | Often explicit | Sometimes implicit | Surges expose weak geometries |

| Power-frequency withstand | Explicit | Explicit | Baseline dielectric margin |

| Creepage distance | Profiled surfaces common | Varies widely | Wet contamination pushes creepage to the limit |

| Air clearance near wall | Controlled by design | Often influenced by external hardware | Hardware can erase margin in mm |

| Terminal interface | Defined stud/pad/lug | May be minimal | Torque and contact repeatability |

| Current rating | Typically explicit (A) | Not always applicable/explicit | If it carries primary current, require an A rating |

| Mounting envelope | Tight definition (cutout/bolt circle) | Variable across vendors | Retrofits fail on mm differences |

| Sealing strategy | Often integrated at wall edge | Often sealing-first | Moisture at wall edge is a common trigger |

A practical discriminator: if you must bolt a busbar/cable lug to a conductor through the wall with a specified torque (e.g., 35 N\cdotpm), you are usually dealing with a wall bushing requirement. If the penetration’s main job is barrier/sealing and the terminals are not the controlling interface, a through-wall insulator can be appropriate—provided withstand and geometry are explicitly stated.

Standards mapping (don’t guess): IEC 60270 (PD measurement method) and IEC 60137 (bushing products above 1 kV) are commonly used references. If you need the governing standard for dielectric test requirements of the metal-enclosed switchgear assembly (as opposed to the standalone part), confirm it before citing.

Map the location to the interface you actually need:

Field reality often penalizes the surface and the wall edge first. Use this checklist to decide when “barrier-only” becomes risky.

A repeatable workflow beats appearance-based substitution.

If you want XBRELE to recommend the best-fit configuration, share your voltage class (kV), wall thickness (mm), terminal style, and environment notes. We’ll map you to the right geometry and acceptance cues: wall bushing options.

Q1: What’s a practical sign that a through-wall insulator might be the wrong choice?

If the design depends on controlled terminal contact pressure and a defined current path, a bushing-style interface is typically lower risk.

Q2: Why can two parts with the same cutout still behave differently?

Surface profile, sealing boundary placement, and the installed hardware edges can shift local stress and wet-surface leakage behavior.

Q3: If PD data isn’t available, what can I tighten instead?

Dimensional tolerances, defined terminal geometry, workmanship controls around inserts, and a disciplined receiving inspection help reduce variability.

Q4: Which field condition most often forces a re-think?

Persistent condensation combined with contamination tends to expose short wet creepage paths and weak sealing boundaries.

Q5: Is wall cutout finish really selection-critical?

Often, yes—sharp edges and burrs concentrate electric stress; controlled deburring and radius are a low-cost way to preserve margin.

Q6: What’s a conservative retrofit approach when drawings are incomplete?

Measure the existing interface in mm, document the hardware stack-up, and avoid assuming interchangeability based on external appearance.