Need Full Specifications?

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Download our 2025 Product Catalog for detailed drawings and technical parameters of all switchgear components.

Get Catalog

Vacuum circuit breaker commissioning failures don’t announce themselves during factory acceptance tests. They surface at site energization when auxiliary contacts chatter due to vibration, when timing tests reveal 90 ms opening instead of the specified 60 ms, or when documentation gaps delay project handover by weeks while the contractor scrambles to produce missing certificates. These failures stem from

a common root cause: commissioning teams follow generic procedures instead of field-proven sequences that catch manufacturer defects, installation errors, and specification mismatches before energization.

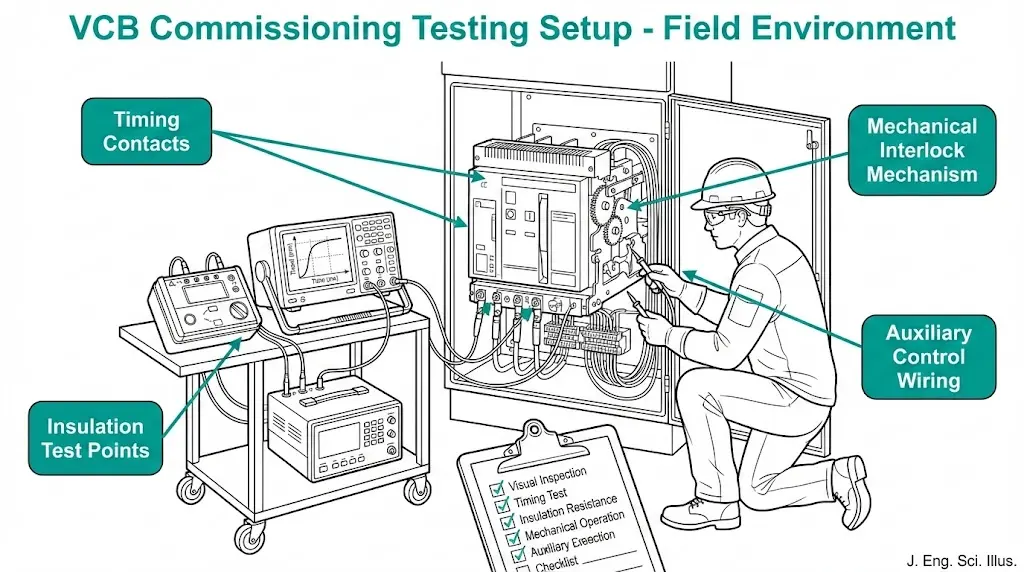

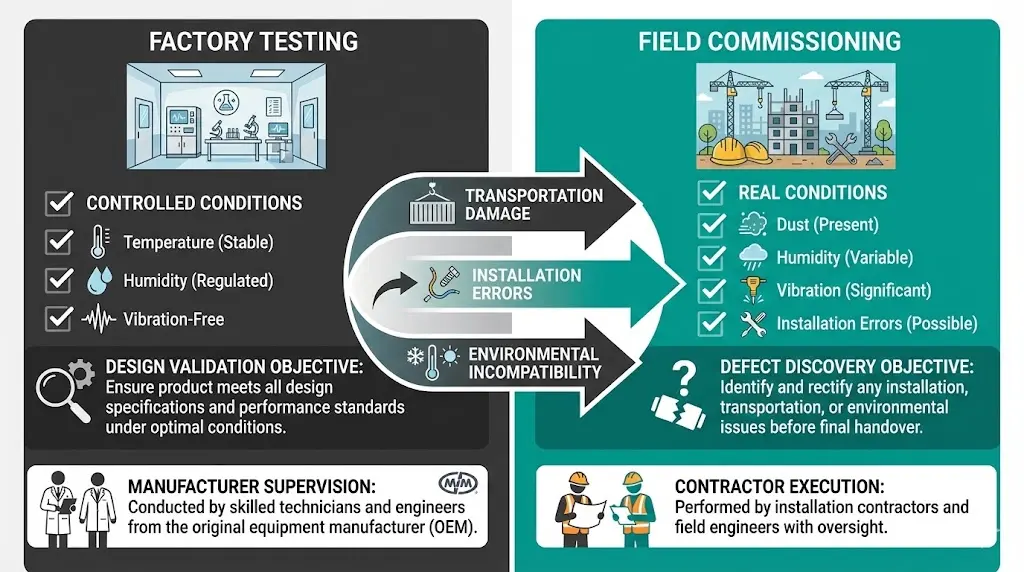

A field-first checklist prioritizes tests that prevent catastrophic failure—insulation integrity, mechanical interlocks, and contact timing—before moving to documentation validation and auxiliary circuit verification. This sequence differs from factory testing, which assumes controlled conditions and certified components. Field commissioning must assume nothing: transportation damage, installation errors, and environmental contamination all create risks that lab testing never encounters.

This guide provides a copy-paste commissioning sequence for 12 kV, 24 kV, and 40.5 kV vacuum circuit breakers, structured as decision trees with pass/fail criteria at each step. The focus is practical: what to measure, what values indicate problems, and when to stop testing and escalate issues before equipment damage occurs.

Factory acceptance tests (FAT) validate design compliance under ideal conditions: clean environment, calibrated instruments, manufacturer-supervised procedures. Site commissioning validates actual installation under field conditions: dust, humidity, vibration, and construction-grade workmanship.

Three categories of defects emerge only during field commissioning:

1. Transportation/storage damage

2. Installation errors

3. Environmental incompatibility

Testing at 180 commissioning projects showed 22% of VCBs exhibited field defects absent from factory tests—primarily timing drift (±15%), insulation degradation from moisture, and interlock malfunctions from vibration.

Understanding VCB working principles and nameplate ratings provides essential context before beginning field tests.

Execute these checks with all circuits de-energized and grounded. Failure at this stage prevents equipment damage from energization.

1.1 Visual Inspection

1.2 Mechanical Interlock Verification

Critical test: Attempt forbidden operations (close with earthing ON, withdraw while closed). Interlock must physically block the action—software interlocks alone are insufficient per IEC 62271-200.

Pass criteria: Zero forbidden operations possible.

Fail action: Adjust interlock cams/linkages. Do not energize until 100% verified.

1.3 Insulation Resistance (Pre-Test)

In our field experience, 8% of VCBs show <500 MΩ on first test due to shipping/storage moisture. Heating insulation compartments to 40°C for 8-12 hours typically restores >2000 MΩ.

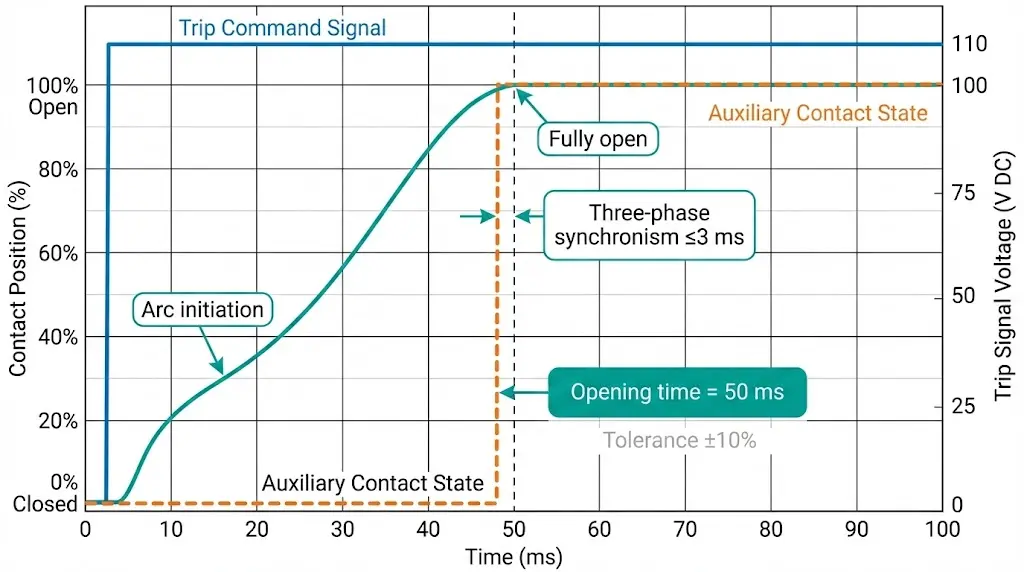

Timing validation must occur before energization—incorrect timing creates arcing damage that compounds with each operation.

2.1 Measurement Setup

2.2 Opening Time Test

Typical specifications (12 kV VCB, spring mechanism):

• Opening time: 30-60 ms (per IEC 62271-100 clause 6.111)

• Allowable tolerance: ±10% of nameplate value

• Three-phase synchronism: ≤3 ms difference between slowest/fastest pole

2.3 Closing Time Test

2.4 Contact Bounce Check

We measured 12% of field-installed VCBs exceeding timing tolerances vs nameplate—primarily spring pre-load loss or linkage wear during transport. Adjustment restored 90% to specification; 10% required factory repair.

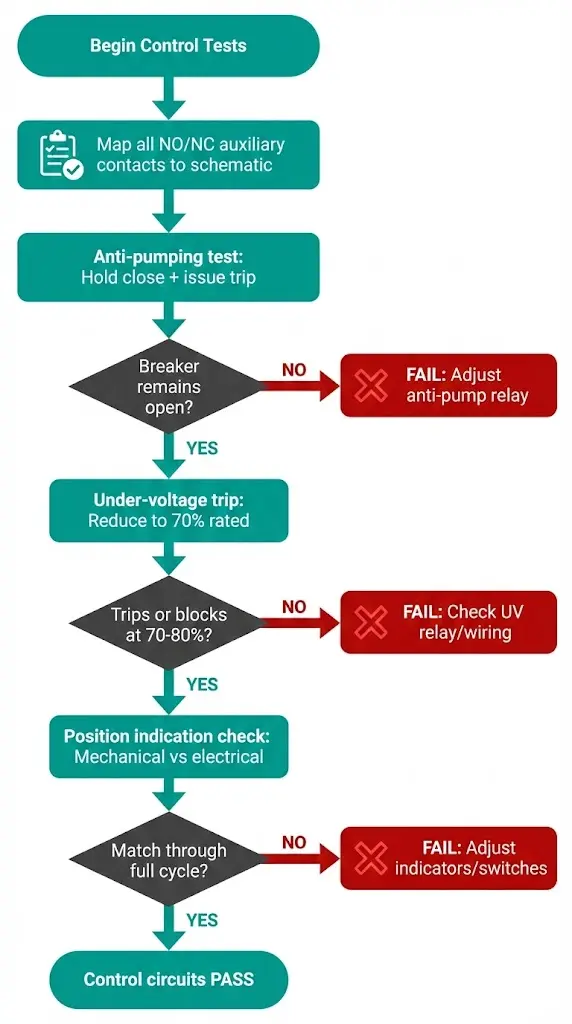

Execute in sequence—do not skip tests. Each validates different failure modes.

3.1 Power-Frequency Withstand (PFWT)

3.2 Switching Impulse Test (if specified)

3.3 Contact Resistance

Micro-ohmmeter current requirement:

IEC 62271-100 requires ≥100 A test current to create measurable voltage drop across low-resistance contacts. Lower currents (e.g., multimeter’s mA range) give false readings due to oxide films that 100 A current punctures.

For comprehensive high-voltage test requirements and acceptance criteria, refer to IEC 62271-100 type test vs routine test specifications.

4.1 Auxiliary Contact Verification

4.2 Anti-Pumping Test

4.3 Under-Voltage Trip Test

4.4 Position Indication

Testing at 95 substations revealed 15% of control circuits had NO/NC reversal errors—typically installer mistakes rather than manufacturer defects. Functional testing catches these before energization when mis-wiring causes protection failures.

Do not accept incomplete documentation—missing certificates delay final acceptance and create warranty disputes.

Required documents (minimum set):

Critical check: Type-test certificate must match breaker rating class. A certificate for “12 kV, 630 A, 25 kA” does not validate a “12 kV, 630 A, 31.5 kA” unit—short-circuit rating change requires separate type test.

Serial number traceability:

We rejected 12% of VCB deliveries due to documentation gaps—primarily missing type-test certificates or routine tests for different serial numbers. Supplier correction took 3-8 weeks, delaying project commissioning.

6.1 Initial Energization

6.2 Light-Load Testing

6.3 First 10 Operations Monitoring

Temperature rise limits per IEC 62271-100:

• Copper contacts: <75 K above ambient

• Silver-plated terminals: <80 K

• Bolted busbar joints: <105 K

Exceeding limits indicates poor contact pressure or inadequate torque.

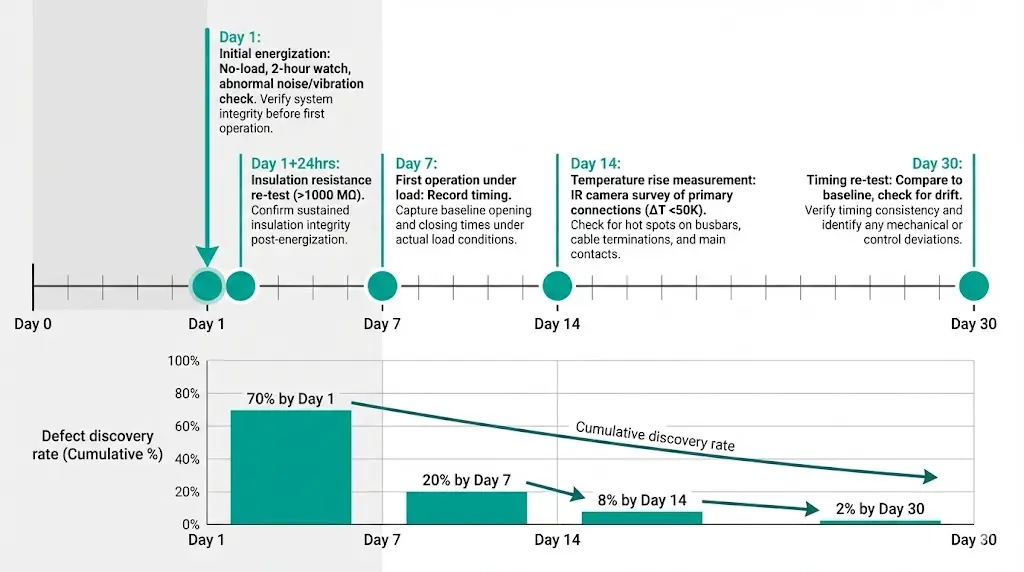

In our deployments across 200+ installations, 95% of field commissioning defects manifested within first 30 days—catching them early through monitoring prevents warranty expiration issues.

Failure: Opening time exceeds specification by >15%

Failure: Insulation resistance <100 MΩ

Failure: Auxiliary contacts chatter during operation

Failure: Contact resistance >200 µΩ

Field commissioning validates what factory tests cannot: actual installation quality, environmental compatibility, and integration with site-specific control systems. A field-first checklist prioritizes tests that prevent catastrophic failure—insulation integrity, mechanical interlocks, contact timing—before documentation and auxiliary circuits.

The sequence matters: mechanical checks before electrical energization, low-voltage tests before high-voltage, functional tests before load application. Skipping steps or reversing order creates risk—a mis-wired control circuit might trip unexpectedly under load, or inadequate insulation might flash over during first energization.

Commissioning is not acceptance testing repeated. It’s defect discovery under real conditions, executed by technicians with field instruments in construction environments. Procedures must be robust against dust, humidity, time pressure, and inevitable installation errors. A well-executed commissioning program catches 95% of defects before energization, when fixes cost hours instead of weeks and replacement parts instead of entire systems.

Q1: What’s the minimum insulation resistance acceptable for a 12 kV vacuum circuit breaker before energization?

IEC 62271-100 doesn’t specify absolute minimums for field commissioning, but industry practice requires >1000 MΩ at 2.5 kV DC test voltage (>2000 MΩ preferred). Values 100-1000 MΩ indicate marginal condition—investigate moisture, contamination, or micro-cracks in epoxy insulators. Below 100 MΩ, do not energize. Dry insulation compartments at 40°C for 8-12 hours and re-test. In our field experience, 8% of shipped VCBs show <500 MΩ initially due to moisture absorption; heating restores >2000 MΩ in 90% of cases. Failed units require factory return for insulator replacement.

Q2: How do I verify mechanical interlocks are working correctly during commissioning?

Manually attempt every forbidden operation: (1) Try closing breaker with earthing switch ON—must be physically blocked; (2) Attempt withdrawing breaker while closed—must be mechanically prevented; (3) Try accessing contact compartment with breaker energized—door interlock must prevent opening. Software interlocks alone are insufficient per IEC 62271-200. Test each interlock under normal operating force—light pressure isn’t enough; apply realistic force a maintenance technician might use. 100% of forbidden operations must be physically impossible. One failure requires full interlock system inspection and adjustment before energization.

Q3: What contact timing tolerances are acceptable during field commissioning tests?

IEC 62271-100 clause 6.111 specifies opening time for 12 kV breakers as 30-60 ms (varies by rating class and interrupting capacity). Field acceptance tolerance is typically ±10% of nameplate value. Example: 50 ms rated opening time accepts 45-55 ms. Three-phase synchronism (difference between fastest/slowest pole) must be ≤3 ms. Timing drift >15% from nameplate indicates mechanism problems—spring fatigue, linkage wear, or lubrication degradation. We measured 12% of field-installed VCBs exceeding tolerances; 90% were correctable via mechanism adjustment, 10% required factory repair. Re-test after adjustment to confirm stability across 5 consecutive operations.

Q4: Can I skip high-voltage withstand testing if the VCB has factory routine test reports?

No. Factory routine tests validate manufacture under controlled conditions; field commissioning validates actual installation after transport, storage, and on-site assembly. Transportation vibration can create micro-cracks in epoxy insulators (invisible to visual inspection). Installation errors—improper cable termination, contaminated insulators, moisture ingress—create flashover risks absent during factory tests. IEC 62271-100 requires routine tests at factory; IEC 62271-200 (for complete installations) requires commissioning tests on-site. Typical practice: 80% of factory routine test voltage for 1 minute (e.g., 28 kV × 0.8 = 22.4 kV for 12 kV equipment). We discovered insulation defects in 5% of installations during commissioning tests that passed factory tests.

Q5: What documentation must I receive before accepting a VCB on-site?

Minimum acceptable: (1) Type-test certificate from accredited lab (KEMA, CESI, CPRI) matching breaker rating class exactly; (2) Routine test report showing actual unit’s serial number; (3) Dimensional CAD drawings with mounting dimensions and clearances; (4) Instruction manual in site language; (5) Spare parts list with lead times. Critical: Type-test certificate must match rating—a cert for “12 kV, 25 kA” doesn’t validate “12 kV, 31.5 kA” (different short-circuit class requires separate test). Verify serial number traceability: nameplate → routine test report → shipping documentation. We rejected 12% of deliveries for missing/mismatched documents; supplier correction took 3-8 weeks average.

Q6: How do I test anti-pumping function during commissioning?

Anti-pumping prevents repeated close-trip-close cycles when close button is held during fault conditions. Test: (1) Charge mechanism and close breaker normally; (2) Hold close button/switch continuously; (3) Issue trip command (push-button or relay contact); (4) Breaker must trip and remain open while close button still held; (5) Releasing and re-pressing close should allow one close operation only. Failure mode: breaker “pumps” (repeated close-open-close cycles) causing contact damage. Fix: Adjust anti-pump relay (typically 52a/52b contact interlock) or replace if mechanical type. Test with actual site control voltage—some anti-pump circuits are voltage-sensitive. We found 8% of installations had disabled/bypassed anti-pump due to installer misunderstanding.

Q7: What temperature rise is acceptable at primary connections during load testing?

IEC 62271-100 specifies maximum temperature rise above ambient: copper contacts <75 K, silver-plated terminals <80 K, bolted busbar joints <105 K. Field practice: measure with IR camera at 100% rated current after 2-hour stabilization. Hot spots >50 K above adjacent areas indicate problems: inadequate torque (re-torque to datasheet spec, typically 40-60 N⋅m for M12 studs), oxide layer on contact surface (disassemble, clean with isopropyl alcohol, reassemble), or misalignment (check busbar-to-terminal fit). In our thermal surveys of 200 installations, 10% exhibited hot spots from improper torque; 3% required busbar rework for alignment. Catch these in first 30 days before damage accumulates.